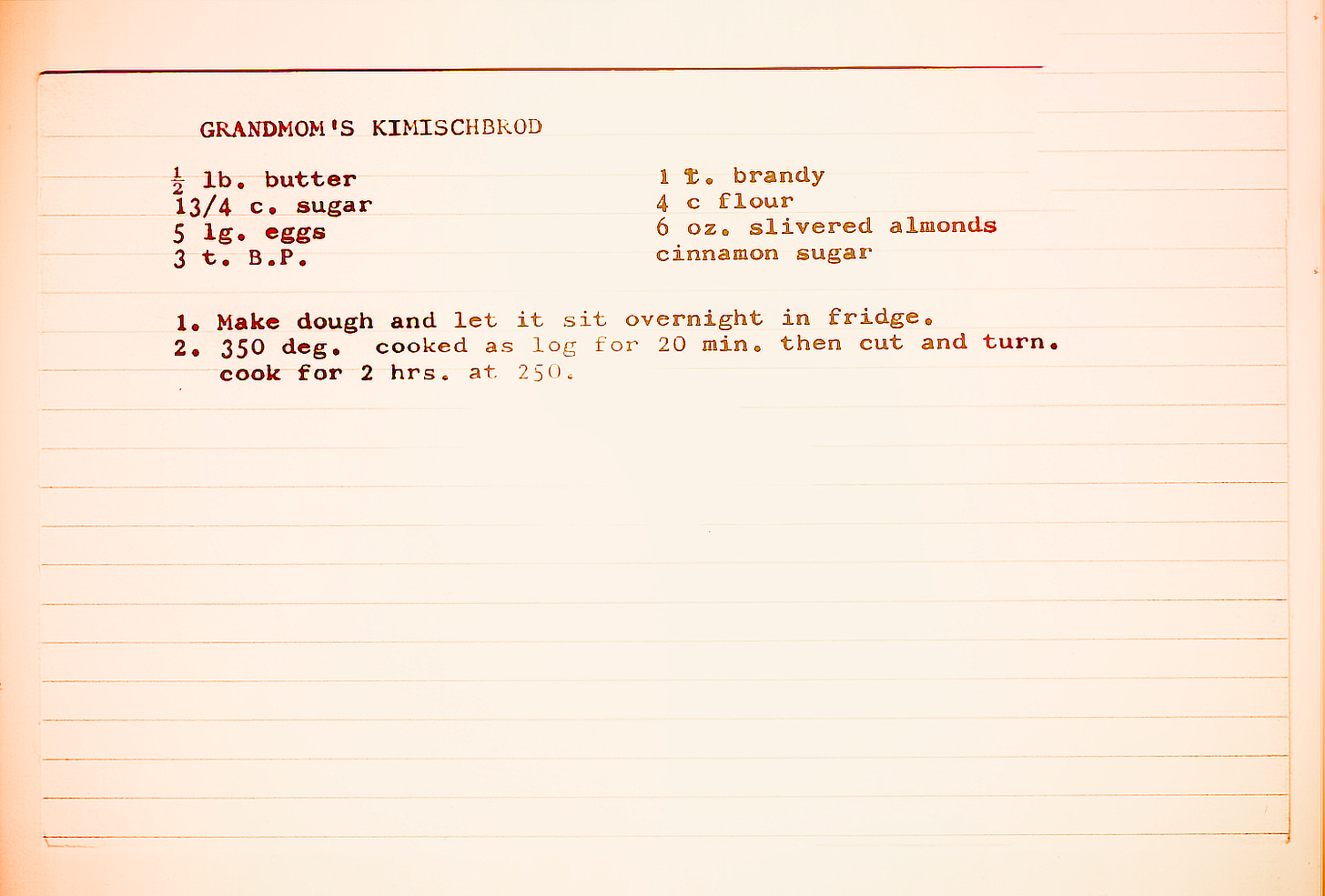

I typed this recipe on an index card at least 40 years ago, long before personal computers existed.

When I was a kid, my maternal grandmother would arrive with a tupperware container full of these crunchy, mildly sweet Russian Jewish versions of biscotti. I loved eating them.

But this is not really a happy recipe. Whenever I come across the digitized image of this card, I’m reminded of my mother’s traumatic relationship to my grandmother and to cooking and food in general. It also reminds me of perhaps the meanest, least generous thing I have ever said to another human being.

Meanness #1

My mother was fat her entire life. She felt a lot of shame and also anger about how she was treated because of being fat. Cooking and eating were not relaxed experiences for her.

My grandmother didn’t make the field of nourishment any easier. She staked out her kitchen as a site of dominance of mother over daughter.

Grandmom was interested in emotional control, not in passing on her passion and skill. She didn’t welcome her daughter into the kitchen. According to my mother, if asked for a recipe, my grandmother would deliberately leave out some ingredient or instruction so that her daughter could not successfully duplicate it.

Consequently, you are advised to try her kimishbrod recipe at your own risk.

Meaness #2

My mother married a fat-phobic, narcissistic man. Some of my worst memories of my father involve the cruel comments he made about my mother’s weight.

As time passed and their marriage deteriorated, he conducted very public affairs with much younger, exceedingly skinny women. I read these as grave and pointed affronts to my mother.

The meanest little word

I always loved cooking. The first meal I ever prepared was roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. I was five years old.

My mom bought me the ingredients, and I just followed the instructions in a Julia Child holiday recipe book. I vaguely remember my grandmother being at that meal.

I also liked to play chemist in the kitchen, mixing things randomly to see what would happen. One particular spice mix involving fennugreek enthralled me. Smelling it induced a kind of magical reverie.

During my twenties, I worked as a pastry chef, prep and line cook, and caterer. I was living in New York City. My mother lived in a townhouse in Philadelphia, thankfully divorced from my father.

My mom was still a 50’s cook. She used a lot of canned, frozen, and pre-prepared foods—the foods of my childhood. By that point, I was a full-blown food snob. My mom was also still anxious in the kitchen.

That particular visit, we were cooking dinner in her kitchen. She was pouring canned kidney and garbanzo beans into a pan.

She turned to me, and with a slight nervous tremor and hint of hopefulness in her voice, she said, “It’s fun cooking together, isn’t it?”

It’s hard to write this, but I only responded with one word: “No.”

I still can feel everything that welled up between my mother and me in the silence after that single, meanest word.

I’m really, really sorry, Mom.

Every single time

I can recall the feeling of heart stinginess and unaccountable resentment that propelled that terrible “no.” I’m not generally a mean person, but I’ve been deliberately mean to others a handful of times in my life. I can remember every single time, and I’ve learned from those memories of meanness.

Meanness is not the cause of the pain that arises in others when we are being our best selves and that just doesn’t happen to be who others want us to be. That kind of pain is unavoidable if we want to grow and be happy.

Meanness is directed toward making others feel small and ourselves protected and defended. It’s a violent ejection of internal pain and uncertainty.

Being mean to others leaves a residue of sadness and poignancy. I wince at the memory of serving to others what I could not digest. Maturing and recognizing my own pain, I can feel the potential for intimacy, not disconnection, that pain makes between us.

Love is freedom

Through my spiritual practice, I’ve also learned something else. Gaining the capacity to genuinely want the best for everyone and to feel love for everyone is a great freedom.

Most people think loving everyone is a good thing. It’s a bit of a cliché. But we don’t realize how much making enemies of others, even just internally, binds up our energy and mind and limits our skill, expressiveness, opportunities for connection, and capacity to adapt.

When we begin to notice our prison, our desire to open our hearts to others grows stronger. At some point, when we are living largely from the heart, we are free to respond in fresh ways that do not bind us. We experience the joy of being generous and being of genuine use to others.

Meanness is a prison.

Love is freedom.

with infinite love,

Shambhavi

Not quite ready to fire up a paid subscription, but want to show your appreciation?

Please join Shambhavi and the Jaya Kula community for satsang & kirtan every Sunday at 3:00pm Pacific. Come in person to 1215 SE 8th Ave, Portland, OR, or join Jaya Kula’s newsletter to get the Zoom link for satsang. You can also listen to my podcast—Satsang with Shambhavi—wherever podcasts are found.

Thank you for telling this. Like an arrow Right to the heart of things. Much love to you.