Over the past two years of intensified genocide in Gaza, some yoga people, Hindu people, and Buddhist people from the West have publicly announced that they feel duty-bound to “witness” the horror.

We in the U.S. and other Western countries are paying for the genocide and are many-handedly propping up a failed, genocidal state. So the bid to be positioned as a witness stands in stark contrast to the reality of our direct complicity and instrumental participation.

We are also experiencing here in the U.S. the ascendance of a dictatorial state.

As does Israel, this state uses violence and terror as primary methods of control.

It starts wars or threatens war in order to remain in power.

It is rapidly enacting racist and misogynist policies and breaks laws to do so.

It is building an even deeper surveillance state and promotes false narratives of success when failure is its real condition.

As I said in a recent podcast:

“This isn’t just about somebody else. You’re not just witnessing something about somebody else. This is about us.

It’s about every one of us. It’s about every one of us in the United States, about every one of us in Western Europe, about every one of us on this planet. Because the whole question of what it means to be human is now globally up for grabs.”

- From Satsang with Shambhavi: “Spanda, Codependence, and Being Untethered,” Dec 3, 2025.

A brief history of witnessing

Sankhya, Vedanta, and Advaita Vedanta are broad and ancient swathes of religious view and practice from India. They span the spectrum from dualistic to non-dualistic views of reality, but they share concepts of God or the Absolute as a witness to manifest life.

Witnessing in Vedanta, Advaita, and Sankhya is most often coupled with an idea of purity and remaining untainted by phenomena. It is associated with transcendence, not immanence, and with stillness rather than activity.

Across various Hindu source texts, witnessing is strongly associated with detachment from the needs of the body, sexuality, emotions, and the outward-moving senses in general.

Two birds

A well-known allegory of the witness appears in the Mundaka Upanishad, a section of the Artharva Veda.

Two birds, companions and friends, nestle on the very same tree. One of them eats a tasty fig; the other, not eating, looks on.

Stuck on the very same tree, one person grieves, deluded by her who is not the Lord; But when he sees the other, the contented Lord—and his majesty— his grief disappears.1

— Mundaka Upanishad, 3.1.1 - 3.1.2

This is considered to be one of the more scholarly translations. It’s debatable whether or not the gendering of the two birds accurately reflects the letter of the Sanskrit text. But it does reflect a near-universal cultural lens through which “she” is the one who cannot control her passions and who “deludes,” while “he” represents the idealized witness who is detached and not subject to desire.

The birds of witnessing and ordinary desires are “companions and friends” because they exist within each of us. The standard contemporary interpretation of this verse is that the suffering human must recognize the witnessing aspect of himself and this will cause the female-coded aspect of the self to cease its indulgences.

The female-coded, and also the dark-skinned and lower-caste, are associated with the body, sexuality, sinfulness and the senses. The male and lighter-skinned and upper caste are associated with the mind, purity, witnessing, the eyes, and with seeing.

Lose the watcher

Various teachings from the traditions I’ve practiced in contain instructions such as “We must lose the watcher,” “We should be free from both the watcher and the watched,” “Unmind the mind,” and “Real darshan (seeing) is without witnessing.”

The triad of the witness, the act of witnessing, and the witnessed is the fundamental protocol of dualistic experience despite the fact that various non-dual traditions from India recommend deploying it.

It works like this. I set myself apart and perform an operation of witnessing life, or my own mind, thus relating to my thoughts and emotions as a kind of othered entity.

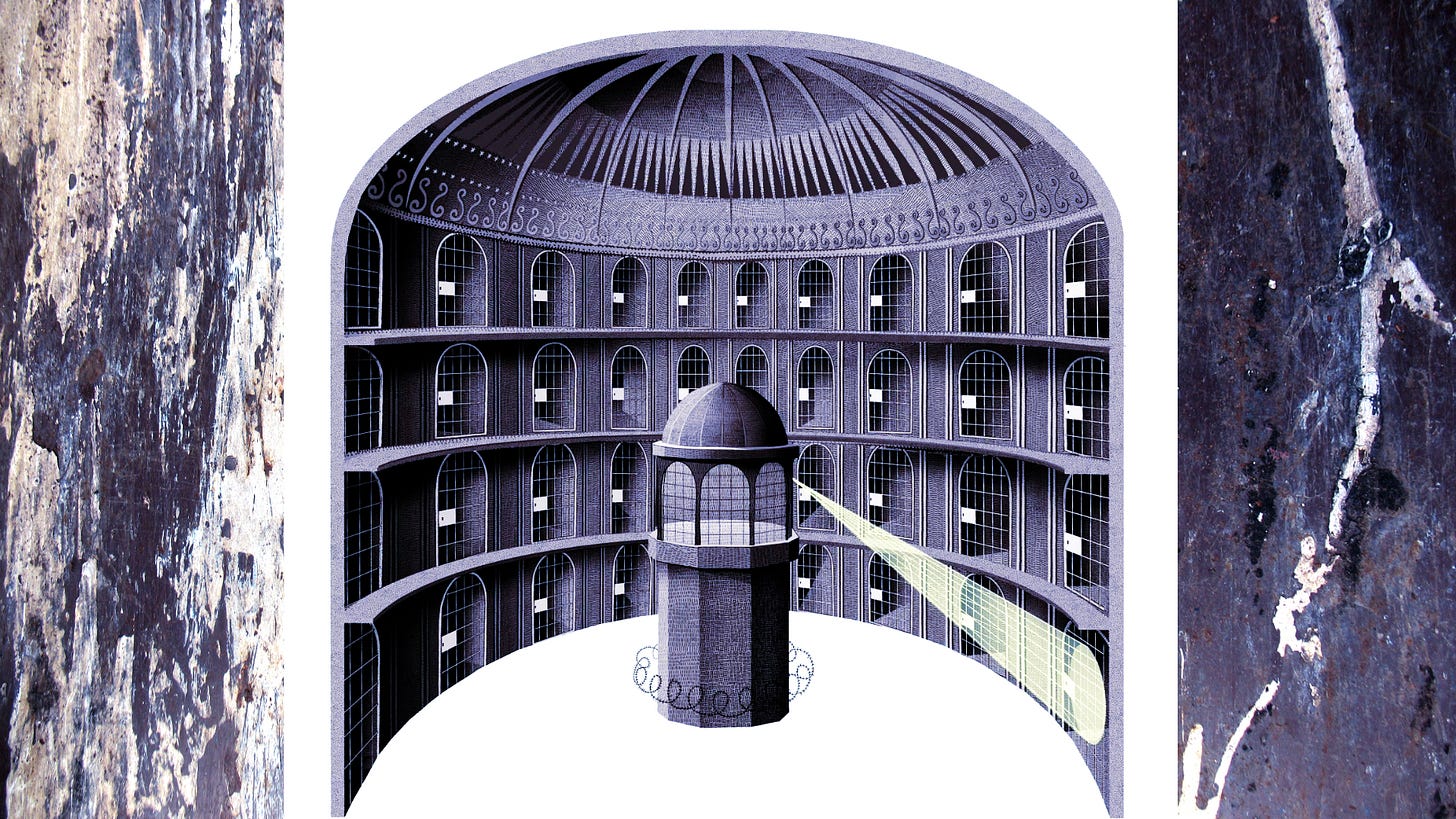

For the witness, the world becomes a panopticon, a tower keeping order over a scene of incarceration.

The panopticon is a privileged view. But what is incarcerated?

Eyes rolling (back)

For the witness cultures of mainstream Hinduism, and to a lesser extent Buddhism, various styles of non-involvement are admired.

These range from literal renunciation to the admiration of insensible states of interiorization or trance, to spiritual practices that encourage becoming unaware of the body or one’s surroundings.

Along this spectrum I would also include what I have called “spiritual botox,” the crude assumption that “detachment” is equivalent to non-feeling or non-expressiveness.

Some Western-derived teachers in the witness traditions are prone to speaking in measured monotones, their facial muscles remaining unnaturally still. They may even move with a deliberate slowness.

This is a performance of a concept of witnessing or detachment.

None of my more realized teachers behaved like this. In fact, they had an enormous emotional range and were the most expressive and spontaneous people I’ve ever encountered. And they laughed wholeheartedly.

The Spiritual Witness Protection Program

The teachings on the witness were more nuanced in general earlier on in their histories. Now, however, we have people actually promoting as spiritual accomplishment the assumption of a stance of faux neutrality or distance from the suffering of others.

Deploying witnessing in this way is one more layer of the protection of privilege: the protection of spiritual “authority,” the protection of reputation, the protection of money.

But what matters to me most is the sequestering or “incarceration” of unbound compassion and kindness.

The Eve of Destruction

When we are busy taking up a position, any position, with respect to others, our access to compassion, to spontaneously being moved, is impaired.

We can take up the position of the watcher. We can take up a position of detachment. We can take up a position of “reasonableness.” We can even take up a position of compassion.

Having done so, we will be more cut off from others, not more intimate.

One of the most important lessons that has been gifted to me in my life as a practitioner is that compassion, mercy, kindness, and tenderness are aspects of the natural state. They are woven into the fabric of an alive aware reality.

These are wild, unbound, magical and magnificent flows that don’t follow the rules we have made up about what they should look like or how to embody them.

Luckily for us, we don’t have to make anything up and in fact cannot cultivate what already permeates all.

What we can do is destroy that which stands in the way of us being naturally moved. We can destroy the watcher. We can destroy our brands. We can destroy our reasons. We don’t need them.

We can relax and let the wisdom of life take us.2

Over the past two years, someone occasionally has asked me if I think it’s spiritual to be political.

These questions are sometimes full of yearning. At other times, they barely hide a degree of disapproval.

But I’m not speaking out because I think it’s the right thing to do, or because I have some justification that allows the political and the spiritual to co-exist.

I’m doing it simply because I am moved to do so, because compassion is. Because I can feel that your life is my life, and we are together in a great intimacy that no one can describe, but it can be lived and known.

Some days I am so full of feeling, words pour out.

Some days I am so full of feeling, I cannot speak.

Whatever is happening, I just let myself be and follow however I am moved.

with infinite love,

Shambhavi

Kindred 108 is 100% supported by readers like you. If you benefit from the offerings here, please consider subscribing. Thank you!

Not quite ready to fire up a paid subscription, but want to show your appreciation?

Please join Shambhavi and the Jaya Kula community for satsang & kirtan every Sunday at 3:00pm Pacific. Come in person to 1215 SE 8th Ave, Portland, OR, or join Jaya Kula’s newsletter to get the Zoom link for satsang. You can also listen to my podcast—Satsang with Shambhavi—wherever podcasts are found.

Patrick Olivelle, The Early Upaniṣads: Annotated Text and Translation (Oxford University Press). 3.1.1–3.1.2, 1998.

This is what the spiritual practices in my traditions are for.

Powerful reframing! The panopticon metaphor cuts straight to the heart of whats wrong with using witnessing as spiritual bypassing. Traditional texts set up this tension between the observing bird and the one eating the fig, but the move here is showing how that very structure can become a prison for compassion. The part about realized teachers having huge emotional range instead of performing stillness is so importnat because it exposes the difference beween actual practice and spiritual theater. When compassion becomes something we position ourselves around rather than something that moves through us naturally, we've already lost the thread.